From disposal cost to resource: How scale unlocks the value of organics recycling

For operations and facilities leaders, managing food and other organic material streams is a persistent cost and logistics challenge. Disposal fees, hauling inefficiencies, environmental impact, and regional regulatory requirements all compound the complexity of handling these materials at scale.

A robust, regionalized collection and processing infrastructure supported by a nationwide operation can convert disposal costs into value. Diverting organics from landfill and transforming these materials into their highest and best use depends entirely on access to the right outlets, permits, and processing capacity.

This article focuses primarily on food recycling and identifying what is considered “organic material” for recycling, and the multitude of sustainable options that set your business up for success.

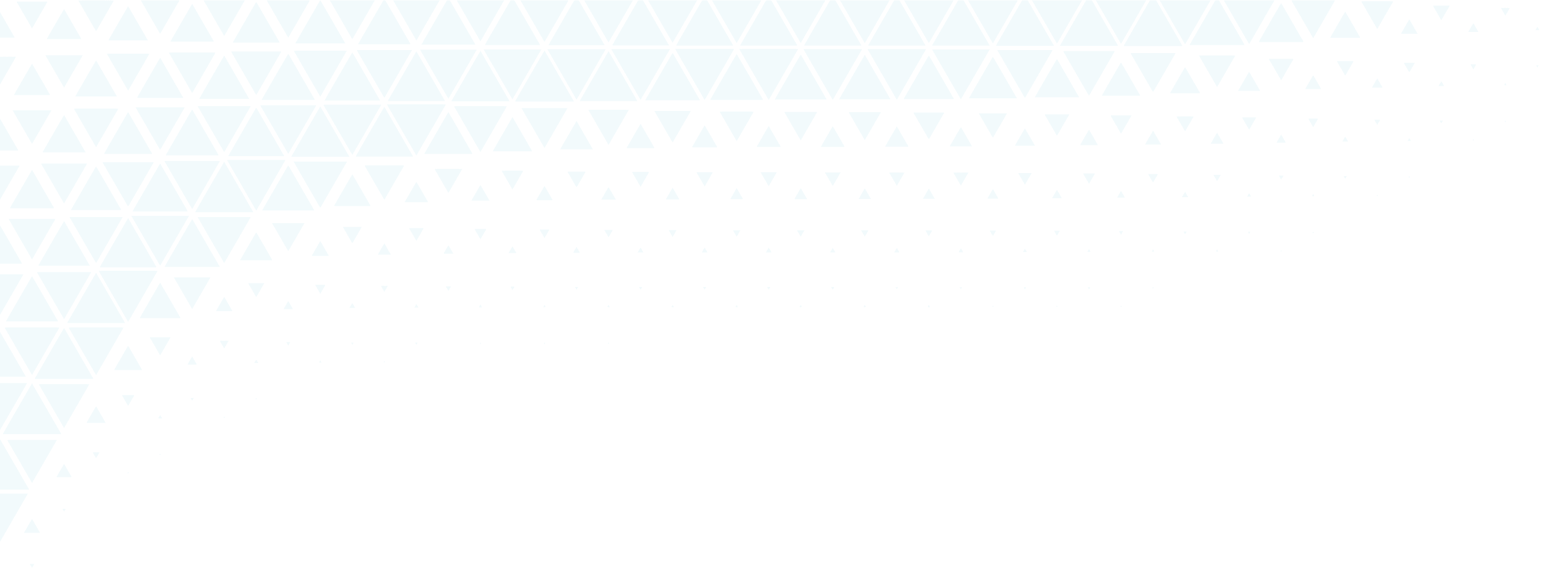

The U.S. EPA's Wasted Food Scale provides a practical framework for comparing management pathways based on the impact to communities and the environment. The scale prioritizes actions that prevent or divert food from disposal, ranking pathways from most preferred to least preferred once unused food is generated.

At the top of the scale are prevention, donation, and upcycling, which keep food in the human food system. When those options are not viable, the scale highlights diversion pathways that recover value from organic material streams, including feeding animals, anaerobic digestion, composting, and land application. Landfilling, incineration, and sending material down the drain sit at the lowest tier because these disposal methods don’t capture the benefits of reusing these valuable, nutrient-rich organic materials.

Importantly, the EPA notes that the Wasted Food Scale focuses on environmental outcomes and does not account for economic or social factors. For businesses, that distinction matters. While the scale helps frame preferred diversion pathways, the feasibility and value of each option depend on regional infrastructure, permitting, type of food or organics, and the ability to operate recycling systems efficiently at scale.

Recycled food creates value for animals

Animal feed made from unconsumed food leverages the food’s nutrients to create a feed product for livestock. Rather than disposing of carb-heavy materials, such as bakery items, bread, and confectionery surplus, these items are processed into feed or, in some cases, directly provided to livestock under regulated conditions.

While formulations vary by animal type, the operational principle remains consistent: usable nutrients are recovered from recycled food and reintroduced into the agricultural supply chain.

By blending recycled feed with standard feed products, farmers can add nutrients at a cost equal to or lower than relying entirely on conventional feed inputs. For food manufacturers and retailers, this pathway creates a dependable outlet for food that cannot be donated while preserving economic value from products that would otherwise represent a disposal expense.

Large-scale composting improves soil health

Large-scale composting is an aerobic (with oxygen) process that converts organic materials, including food, yard scraps (green waste), and, sometimes manure, into a naturally nourishing soil amendment through controlled decomposition.

This process relies on large volumes of organic materials and can be done in piles, rows, or vessels. Commercial composting facilities vary significantly in their acceptance criteria. Most facilities accept yard waste ("green waste"), many accept food waste, and most of those should accept certified compostable products. Facility capabilities are dictated by permits, equipment, and local infrastructure.

The finished product is compost, which creates measurable downstream benefits. When used by farmers, landscapers, and gardeners, compost reduces reliance on synthetic fertilizers and improves soil structure and water retention. These characteristics translate into long-term soil productivity and robust yields.

Anaerobic digestion captures energy and manages solids

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is an enclosed, oxygen-free process that produces two outputs of value: biogas and digestate.

AD utilizes an enclosed system of digesters using microbes to break down food waste, generating biogas, primarily methane, which is a renewable energy source. The remaining material, digestate, consists of solids and water that microbes cannot further break down.

Operationally, AD systems require careful management. The biological process depends on maintaining a precise balance of feedstock type and volume to maximize methane production. The microorganisms are often very specific as far as their preferences, making feedstock consistency a critical factor in efficient operations.

Land application replaces synthetic fertilizer with organic byproducts

Land application allows organic byproducts to be beneficially reused as fertilizer or soil amendments on farms . The primary purpose is soil enrichment or replacement of synthetic fertilizer inputs.

The most common organic byproducts that are beneficially reused for this purpose are food processing residuals. According to the EPA, land application has been practiced for decades and remains the most common recycling method.

Application of these natural byproducts to the land offers several advantages, including improvement of soil health and water holding capacity, less run-off, and slower release of nutrients as compared to synthetic fertilizers. These characteristics can reduce fertilizer input costs while supporting more stable soil performance over time and is another example of the circular economy in action by replenishing the earth with organics.

Scale and systems drive the financial value of organics recycling

Each of these landfill diversion pathways preserves value and improves the environment. Landfilling and incineration eliminate value and contribute to climate change.

The difference between saving money and value creation lies in scale, logistics, and system efficiency. Infrastructure access determines what is possible. Execution at scale determines what is profitable.

To understand how collection density, routing efficiency, and processing technology create financial value for businesses across the U.S., read: Inside Denali's Organics Recycling Network: How Scale Turns Waste Into Value.

At Denali, we work with customers to design landfill diversion programs based on organic material characteristics, infrastructure, and operational goals. Contact us to get started.

Learn more about Denali's services

Join thousands of businesses turning unsold food and organic waste into valuable new products. Partner with Denali for reliable service—and drive meaningful, sustainable impact.